Kim Hjelmgaard, USA TODAY

– Published 5:00 AM EDT Sep. 30, 2021 Updated 3:28 PM EDT Sep. 30, 2021

Lt. Alex Cornell du Houx has dodged a sniper’s aim, rocket fire and a roadside bomb. In some ways, the former U.S. combat Marine’s latest mission, an entirely volunteer one, has been his most challenging: helping at-risk Afghans escape the Taliban.

For the past six weeks, Cornell du Houx, now a Navy public affairs officer, has been part of a definitely-not-ragtag volunteer rescue force that swiftly mobilized amid the U.S. withdrawal.

After the Taliban captured Kabul, Afghanistan’s capital, on Aug. 15, U.S. and coalition aircraft combined to evacuate more than 123,000 civilians in the two weeks that followed, according to Gen. Kenneth McKenzie, commander of U.S. Central Command.

But many more Afghans – either through a lack of a visa, insufficient contacts or bad luck – were effectively marooned in newly hostile territory.

They were, or remain, in peril from reprisals from the new Taliban government because of links to U.S. and NATO forces, foreign aid groups and overseas media. They championed democracy, civil society, education, culture.

Motivated partly by concern at the way the U.S. withdrawal left so many behind – women’s rights activists, translators, journalists, politicians, Afghan National Army pilots, judges and female athletes – a volunteer coalition formed.

“It was the least we could do. We worked and, in many cases, served alongside these people for years,” said Cornell du Houx, 38, who combines work as a U.S. Navy public affairs officer with a civilian job running a nonprofit organization called Elected Officials to Protect America to address security issues related to climate change. He conducted the rescue operations as a volunteer in his civilian capacity.

U.S. military personnel, Washington political veterans, intelligence community members, humanitarian aid workers, even an investment banker from Florida – pooled resources, contacts and knowledge to get Afghans evacuated on military and civilian flights to the U.S., Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

In fact, for about a week in mid-August, Cornell du Houx’s newly founded group, EVAC (Evacuating Vocal Afghan Citizens), and other groups with names like Digital Dunkirk, Team America and Operation Eagle set up an ad hoc “command center” in the Peacock Lounge conference room of the Willard InterContinental Hotel in Washington.

The various units worked together, but also separately, on a dizzying array of logistical challenges ranging from chartering planes to securing landing rights in places such as Albania, Ukraine and the United Arab Emirates. They vetted local bus drivers to take people to Kabul’s international airport. They collected information on how to prioritize evacuees, knowing all the while these decisions could spell life or death and that many people were equally deserving of evacuation.

They also raised money, joined calls with U.S. administration officials and dealt with the panic and fear of Afghans who were trying to escape the Taliban. In some cases, volunteers provided step-by-step instructions to evacuees, advising them on which of the airport’s gates were open, what security precautions to take. They gave guidance about visas and paperwork.

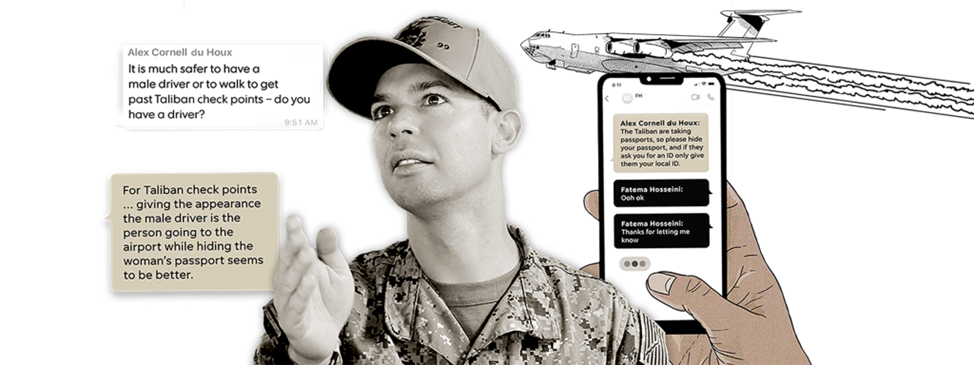

Cornell du Houx had gone through a similar process in helping Afghan journalist Fatema Hosseini, who worked for USA TODAY, to escape with the aid of Ukraine’s special forces – and, a week later, her family. In both cases, he stayed up through the night to relay intelligence, coordinate with U.S. and Ukrainian commandoes on the ground in Kabul, and provide real-time tactical and emotional support to Hosseini and others as they navigated gunfire, tear gas and dangerous overcrowding around Kabul’s airport.

“The whole thing was a rollercoaster ride, very tense,” said Cornell du Houx. “I am trained to know what to do in combat situations but this was something else.”

Iryna Andrukh, a colonel in Ukraine’s military who alongside Cornell du Houx helped orchestrate Hosseini’s rescue, then deployed to Kabul as part of a daring mission to save her family and dozens more, said of her country: “We always save those who are in trouble and ask for help.” As part of that operation, Andrukh helped clear a path for buses to enter Kabul airport. This involved venturing into Taliban-held territory.

Backstory: How a Navy officer, a Ukrainian colonel and a USA TODAY reporter helped an Afghan journalist escape the Taliban

That success inspired EVAC, which Cornell du Houx estimates has now evacuated more than 500 people. It still has a database of about 5,000 names of people seeking a way out.

Scott Mann, a retired U.S. Army Special Forces officer who led a similar volunteer group named Task Force Pineapple, described his team’s efforts to help Afghans in a video message to supporters last month as an “underground railroad.”

The command center in Washington was partly funded by Zach Van Meter, a private-equity investor from Naples, Florida. Van Meter felt compelled to get involved after a friend and business associate of his, a former U.S. Army commando whom Van Meter in an interview would identify only as “Sean,” had reached out and said he knew of about 3,500 children, many of them orphans, who were stranded in Kabul.

“He asked me if I could help save lives. In that context I don’t think anybody could really say no to that. I didn’t really know what it entailed. I don’t think anybody really did,” said Van Meter, who leveraged his business contacts in the Middle East to assist the assembled volunteers.

Van Meter said his collaboration with the volunteers has altered his worldview.

“I’ve met so many people that don’t live like I live, which was, you know, money, capitalism, sort of just push, push,” he said. “They live to save lives. They live to improve humanity. And so I now realize that part of my journey for the rest of my life is going to try to be more purposeful.”

A former U.S. Marine who had specialized in Special Forces reconnaissance was part of a 12-man American volunteer team that deployed to the Kabul airport Aug. 20. The former Marine, who declined to be publicly identified because he did not want to compromise continuing operations, said his group worked with U.S. military and high-ranking contacts in the United Arab Emirates to provide humanitarian assistance to an estimated 12,000 at-risk Afghans who eventually were evacuated to Abu Dhabi.

USA TODAY reviewed a series of communications involving the former Marine’s sources and his association with the evacuation effort, which appeared to support his account.

“We knew all too well the likelihood that America would abandon these people, and we were called into action to do the right thing … to take care of those who had helped us,” the former U.S. Marine said.

In all, about 3,000 volunteers from Alabama to Oregon helped Afghans escape in the days after Kabul’s fall to the Taliban, according to Heather Nauert, a former spokesperson for the U.S. State Department who has been working with volunteers and veterans organizations to ensure safe passage out of Afghanistan for families connected to the U.S. military.

“In many cases it was just suburban dads or moms like me making dinner in the kitchen for their kids, then jumping into action to see what we can do to help,” said Nauert, who described herself as someone who could “help shepherd cases” by filling out paperwork for people to get on flight manifests, calling senators’ offices and flagging particular cases to senior officials at the U.S. State Department and Department of Defense.

The Biden administration has come under criticism for a chaotic withdrawal that left many American allies and civilians vulnerable.

Rep. Ruben Gallego, an Arizona Democrat who chairs a congressional committee on intelligence and special operations, acknowledged that the “pullout could have been handled better.”

A former U.S. Marine who served in Iraq, Gallego spent several sleepless nights in mid-August contacting four-star generals and pressuring the State Department to get people to the airport in Kabul. He assisted volunteers with intelligence about road conditions and explored options to take evacuees to third countries, such as Qatar.

But Gallego said the evacuation represented “the best of America, whether it was the government or whether it was our our civilian side working together (with the government).”

The White House approved a plan for the Biden administration to formalize work with the network of volunteers, according to several volunteers familiar with the matter. This new public-private partnership followed a recommendation to the White House by the U.S.’s top military officer, Joint Chiefs Chairman Gen. Mark Milley.

Gallego is not directly involved with that effort. However, he said he expected it will be “a good way to get organized, help break through bureaucracy, and do a good effort to get people out of out of the country.”

Cornell du Houx is not waiting around for that to happen.

Shortly before this story published, he sent a WhatsApp message to USA TODAY:

“You can add to the count,” he wrote. “We just got 70 kids and 30 adults to safety.”

View the full story at:https://www.usatoday.com/in-depth/news/world/2021/09/30/afghanistan-evacuation-fatema-hosseini-escape-taliban-checkpoints-kabul-airport/5822817001/

No responses yet